- 7 days ago

- 8 min read

From the climb of 660 steps to hidden legends carved in stone, journey with us into the cultural heart of Ondo State’s most breathtaking landmark

We arrived in Idanre just after dawn, when the mist still clung to the granite and the town was waking to the soft rattle of market carts. The hills stood like sentries—layered, immovable, and patient—holding centuries on their backs. Our guide smiled the way people do when they are about to introduce you to an old friend. “People lived up there for more than eight hundred years,” he said, pointing to the skyline of stone. “They only began to come down between 1928 and 1933.” In that moment, the climb stopped being a hike and became an invitation into a living archive.

The 682 Steps

The stairway begins as a promise and quickly becomes a test. We counted each of the 682 steps, the way travelers count heartbeats, with five resting points cut like commas into a long sentence. Children sprinted past us; elders moved with the deliberate economy of those who understand granite and time. The rock was warm in places and cool in others, a pulse moving under the sole.

At the top, just beyond the last riser, the first structure that greeted us was the tourist chalet—the first breath after a long swim. Our guide tapped his walking stick on the ground. “Here, you’re about 3,000 feet above sea level.” The air felt cleaner, like the world had been rinsed. We could look down and trace the lines of new Idanre—the palace roofs, the tight weave of streets, the curve of farms—while the old city waited behind us, intact in its silence.

A Town Carved in Stone

The old settlement spreads across roughly 50 square kilometers of highland, a labyrinth of paths, courtyards, shrines, and living rock. We learned quickly that this wasn’t a ruin. It was a city paused—its rituals, punishments, and poetry preserved in stone.

An elder later told us, “On this hill, twenty-five kings ruled before the people moved down. The twenty-fifth led the last great descent. The twenty-sixth reigned forty-seven years and joined the ancestors only last year. We are watching the horizon for the twenty-seventh.” His voice made the years feel stacked like slabs of slate—countable, solid.

Dagunro: Stop War

Our first historical checkpoint was Dagunro, which translates as “Stop War.” It was once a guard post, a filter through which strangers and threats had to pass. Here, messengers would sprint ahead, warning the palace and the warriors that movement was at the gates. “If trouble slips past here,” our guide said, “it cannot pass the next.” You could feel a tactical intelligence in the landscape: the way the paths narrow, the blind corners, the hidden perches. The hills were both home and fortress.

Ojimoba: The Rock That Waits

From the chalet, our guide raised his stick and pointed to a rock face in the middle distance. “Ojimoba,” he said. “It saved us once.” The story is an old one: hearing of an invasion, the townspeople addressed the rock and, according to legend, it flattened and bore fruit, luring the exhausted invaders to rest. When they lay upon it, Ojimoba erupted and swallowed them. “If you listen at night,” the elder added, “you can still hear voices inside.” Whether you call it myth or memory, the terrain here is an accomplice—no mere backdrop.

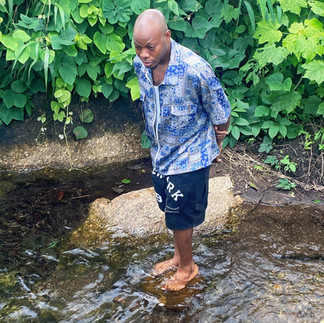

Arun: The River of Medicine

We found the Arun River tucked between boulders, bright and cold as glass. The water is said to heal illnesses—a therapeutic stream in the old days and a place where people still drink and swim. Our guide cupped his hands and took a sip with the simple reverence of habit. “Not everything needs a shrine,” he said. “Some things heal by simply existing."

Letters and an Ark That Isn’t

Along one path, we were shown the “unreadable letters”—mysterious inscriptions locals call Ẹdiẹ kawe, oyinbo kati. Nobody could read them for us; nobody could ignore them either. They hold attention the way a half-remembered dream does. Nearby is a rock formation the townspeople call the Ark of Noah. It is not a claim to the biblical ark, but a granite hull shaped by time into a vessel’s form—enough to suggest rescue and flood, enough to keep the imagination busy.

Apara: Thunder Water

We reached Apara, the Thunder Stream, where warriors were said to drink before battle. The rule was stark: if the water satisfied you, it meant the gods would return you home; if it did not, your fate was sealed. One of us asked, “What if a man lies and claims satisfaction?” The guide didn’t blink. “Then he only leaves, and does not return. Better for such a man to leave a legacy at home before he goes.” In places like Idanre, water is never just water; it is grammar and verdict.

The Narrow Way: Ẹsẹoogbeji

There is a passage here called Ẹsẹoogbeji—a corridor so narrow that two people cannot walk through it side by side. In the old days you signaled before entering; otherwise, one would have to back out, and backing out was forbidden. Worse, the path is flanked by valleys on both sides. A wrong step or a shove, and the hill would decide the argument permanently. The lesson has lingered: in Idanre, the land enforces etiquette.

Missionaries, an Evil Forest, and a School

The missionaries came with books and hymns, and the town, cautious, sent them to the “Evil Forest”—a test as old as suspicion. The forest did not swallow them. The people renamed it Igbore and built what became the first primary school up here in 1896: Igbore Community Primary School. It was later moved down and is now known as St. Paul. The walls are quiet, but you can almost hear slates tapping and alphabets recited against the wind.

Odeja: The Market and the Law

We stepped into Odeja, the old market square, where trade smelled of spice and palm oil and arguments were settled with the efficiency of people who cannot afford to hold grudges. Around it, three stones of power are set like anchors:

The Customary Court, where verdicts once leaned more on reputation and memory than paper.

The Mausoleum, where kings were taken to meet the protocols of farewell.

Okèmògùn, a sacred stone only the king may step upon, and only once a year. The warning is not a metaphor: outsiders who touch it are said to become living dead—caught between worlds. When the king mounts the stone, he does so wearing Ade Ide, the original crown of Odùduwà, and he prays for Idanre and the wide cloth of Yorubaland. “Power,” the elder whispered, “must be heavy enough to bow the head.”

Chiefs’ Quarters and the Stone of Marriage

We walked down Chief Ojomu Street, past the houses of Chief Ojomu, Chief Osolo, Chief Lorin, and Chief Odofin. At one doorway we were shown a boulder called Ẹshọkogbe. Tradition says that a young man must lift it to his chest to prove he is ready to marry. We tried and laughed and failed and argued with the stone, which did not care. “Marriage,” the guide grinned, “isn’t for weak arms or weak hearts.”

We were fortunate to meet Chief Odofin himself. He welcomed us with the gravity of someone who has kept watch longer than the newest houses have stood. He poured a blessing over our journey, the words thick like palm oil, the cadence older than a calendar.

Chief Lorin’s Threshold

At Chief Lorin’s house, the protocols are absolute. No clothing beyond what the custom permits, no handshakes, and if you carry a load on your head, you do not steady it with your hands while within his precinct. The rules feel strange until you understand they are not about modesty or difficulty; they are about power shifting the air around certain doors.

Oke Asunrin and the Wonderful Rock

We reached Oke Asunrin, named for Chief Asunrin, the hunter who first traced these routes. The hill keeps a rock locals call “Wonderful Rock”—a monolith leaning in such a dramatic poise that any other thing would have toppled long ago. It has paused mid-fall for generations, a reminder that balance is sometimes a pact, not a posture.

The Palace: Three Doors and a Calendar of Skulls

The Ancient Palace stands with the kind of symmetry that teaches respect. There are three entrances: one for the king, one for the queen, and one for the people. Inside, we saw the throne, pillars carved into human forms, and a ritual technology of time.

“In the old days,” said our guide, “there was no paper calendar here. Each year, a cow was brought to the palace on a fixed day. Its skull was kept.” When a king died, the skulls were counted. That number marked his reign. It sounds brutal until you realize it is also accurate: a calendar anchored in the undeniable arithmetic of bone. Some practices survive because they do not lie.

Agboogun’s Footprints: Judgment in Stone

We did not reach it—the journey would have taken us another hundred meters down a punishing descent from Agaga Hill—but the legend walked with us: Agboogun’s Footprints, the stone impressions said to belong to the first king who ruled atop Idanre. Oral history calls them magical: they fit the feet of the old and the young alike. In troubled times, a suspected witch or sorcerer would be tested there; if the footprint did not match, death waited near the verdict. Our guide’s face went still as he spoke. “We do not celebrate those judgments,” he said. “We remember them, so we do not return to them.” The past, here, is both a teacher and a warning.

Orosun: The Festival of Ascent

Idanre’s great festival is Orosun. Priests climb to the high places, some for twenty-one days, others for fourteen or seven. They dress in white wrappers, a public vow to purity. On the sacred day, no blood is spilled—if sacrifices are to be made, they are done the day before. On the festival’s peak, the priests vanish into the mountain and return with prayers like rain. To witness Orosun is to watch a town rehearse its covenant with the hills.

A City That Descended, A Memory That Stayed

History here is not a museum—it is a map of decisions. When the hilltop city began to descend in the early twentieth century, it was not abandonment. It was adaptation. The stone kept a portion of the people’s mind, and the town below kept a portion of their feet. You see it in the way the new palace orients itself toward the old; you hear it in the stories that begin with “Up there, we…”

What the Hills Taught Us

We did not cover everything—no one does, not in one day and not in one lifetime. Idanre is too wide, too layered. But we climbed the 682 steps and stood where sentries once listened for trouble. We drank at Arun, stared at Ojimoba, whispered at Apara, shuffled through Ẹsẹoogbeji, learned the laws of Odeja, tested ourselves against Ẹshọkogbe, and watched the palace hold time in the sockets of skulls. We heard of Agboogun’s footprints and felt the tug of a path we could not take—this time.

On the way down, the steps felt different. The same numbers, new meaning. Idanre had moved us from curiosity to respect, from sightseeing to witness. Our guide tightened his wrapper and said, quietly, “The hill remembers those who greet it properly.”

We left with knees that complained and a silence in the chest that did not. Some places exhaust your body and strengthen your memory. Idanre Hills is one of them—a city in the clouds that teaches anyone willing to climb that history is not behind us. It is above us, waiting, step by step.